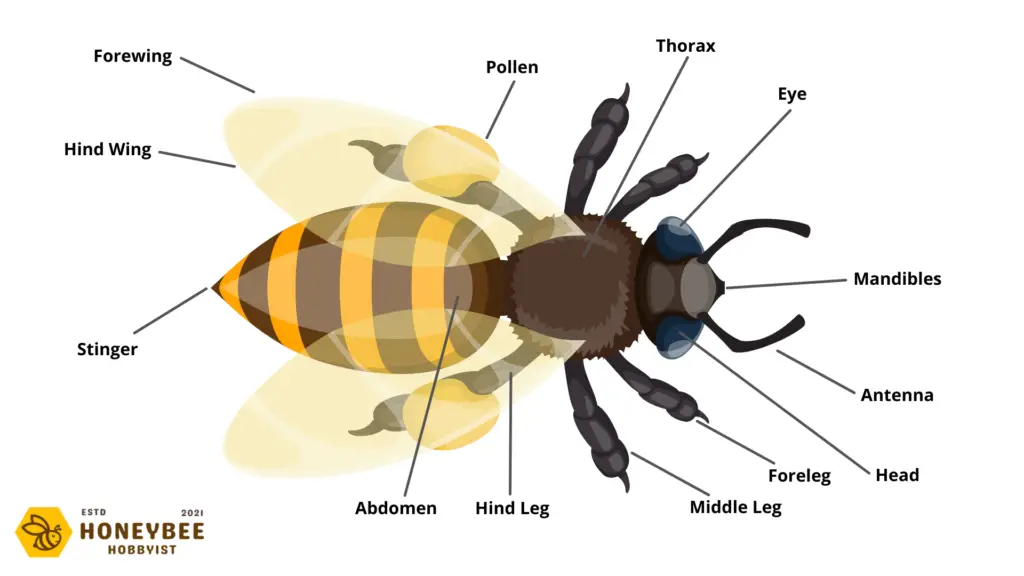

Honey bee anatomy features five unique characteristics to help tell them apart from other insects.

- Exoskeleton – an outer shell that keeps the body protected.

- 3 primary body parts – the head, thorax, and abdomen are easy to distinguish from other body parts

- 2 large antennae – both attached to their head.

- 3 pairs of legs – 6 total legs to help them walk.

- 2 pairs of wings – 4 total wings to help them fly.

The honey bee anatomy diagram below provides a clear snapshot of these five anatomical elements.

Coolest Parts of the Bee

Compound eyes: Honeybees have two large compound eyes, which are made up of thousands of tiny lenses called ommatidia. These eyes help bees detect movement, light intensity, and color. They also have three simple eyes, or ocelli, on top of their head that help them perceive light intensity and navigate using the sun.

Antennae: Bees have two antennae that function as their primary sensory organs. These antennae contain receptors for detecting odors, tastes, vibrations, and even humidity levels.

Proboscis: The proboscis, or “bee tongue“, is a long, flexible tube that allows them to drink nectar from flowers. It functions like a straw, and when not in use, the proboscis can be neatly folded under the bee’s head.

Wings: Honeybees have two pairs of wings, with the larger forewings and smaller hind wings connected by a row of hooks called hamuli. These hooks allow the wings to work in unison, providing lift and maneuverability during flight. Bees can beat their wings up to 200 times per second, allowing them to fly at speeds of around 15-20 miles per hour.

Legs: Bees have six legs, each with specialized functions. The front pair of legs have small notches for cleaning their antennae, while the middle and hind legs are adapted for gathering and carrying pollen. The hind legs have a structure called the pollen basket, or corbicula, for storing collected pollen.

Stinger: Female worker bees have a barbed stinger, which they use as a defense mechanism when they feel threatened. When a bee stings, the barbed stinger is often left behind, along with a venom sac and muscles that continue to pump venom. This injury ultimately results in the bee’s death.

Wax glands: Worker bees have specialized glands in their abdomen that secrete wax. They use this wax to build and repair the honeycomb, which serves as the hive’s structure and storage for honey and pollen.

Spiracles and tracheae: Bees don’t have lungs; instead, they breathe through a series of tiny holes called spiracles along the sides of their bodies. These spiracles connect to a network of tubes called tracheae that carry oxygen throughout the body.

How Bee’s Evolved

The current scientific consensus suggests that bees evolved around 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period.

Before this period, plants reproduced just as conifer trees do today. They release seeds that, when pollen comes into contact with them, become fertilized.

Some plants, known as angiosperms began producing flowers. These flowers needed insects and other animals to deliver pollen from a plant’s anthers (male structures) to their stigmas (female structures).

Bees evolved to take on the flower pollination responsibilities becoming herbivores consuming pollen and nectar, all while fertilizing flowers.

Bees, wasps, and ants carry similar traits, meaning they all are classified as Hymenoptera, meaning “membranous wings”.

Exterior Elements Of Honey Bee Anatomy

| Head | The head is where all visual, gustatory, and olfactory inputs are received and processed. |

| Mandibles | Bee “teeth” are not like humans in that they are not enameled. They are used to bite, chew, carry, and protect the hive. |

| Proboscis | The “bee tongue“, or tube-like mouthpart is used to suck in nectar, pollen, water, honey, and other food. |

| Ocelli Eyes (Simple) | Three simple eyes use one lens with several sensory cells and can detect light but not shapes. |

| Eye (Compound) | 2 compound eyes help the bees see ultraviolet markers of the flowers that store the nectar they’re on the hunt for. |

| Antenna | 2 antennae house thousands of sensory organs giving the bee its power to touch, taste, and smell. Click here to learn about what attracts and repels bees. The antennae also sense sound with the help of the hairlike mechanoreceptors that sense the movement of particles in the air. |

| Thorax | The midsection, or center of locomotion, where the (6) legs and wings attach. |

| Abdomen | The hind part of the bee and where the stinger is located. |

| Stinger | Or sting is a sharp organ at the end of the bee’s abdomen used to inject venom. |

| Forewings | The larger wings are closest to the bee’s head. |

| Hind Wings | Wings farthest from the head. These wings are synchronized in flight with the forewings using a row of wing hooks that attach to the rear edge of the forewings. |

| Forelegs | Legs closest to the head. These legs often clean the bee’s antenna. |

| Antennae Cleaners | Notches filled with stiff hairs that help bees clean their antennae. There is one on each foreleg. |

| Middle Legs | Leg located between the foreleg and hind leg. |

| Hind Legs | Legs farthest from the head. In workers, these legs have a unique set of tools used to collect and carry pollen called the press, brush, and auricle. |

| Coxa | The first segment of an insect leg. |

| Trochanter | The second segment of an insect leg. |

| Femur | The third segment of an insect leg. |

| Tibia | The fourth segment of an insect leg; the tibia of the hind leg holds the pollen basket, where pollen is carried. |

| Metatarsus | The fifth segment of an insect leg; the metatarsus of the hind leg holds special pollen-collecting tools. |

| Tarsus | The last segment of the leg and what touches the walking surface. |

| Tarsus Claw | Claw found on the last segment of the leg. |

Bee Wings

Bees have two sets of wings (4 total) on either side of their bodies. They’re held together by hamuli, comb-like teeth, that allow them to act as one large surface.

For many years, there was no scientific consensus on how bees could fly. By using high-res video imagery, they discovered that bee wings were not rigid like airplane wings. They have the ability to twist and rotate with a quick sweeping motion.

Although this motion was thought to be inefficient, it actually allows bees to carry heavy loads. This is especially helpful for honey bees which carry nectar and pollen.

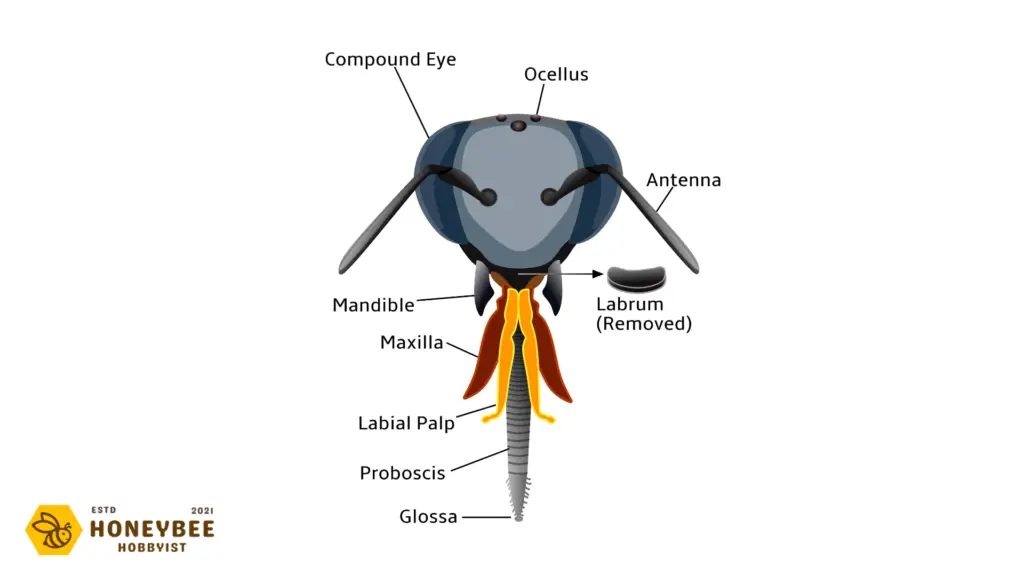

Head & Facial Elements Of Honey Bee Anatomy

Bees have 5 total eyes and two types of eyes. Two compound eyes on the side of the head and three simple eyes on the top of the head. Click here to learn more about the bee’s eyes, eyesight, and extra sensory abilities.

| Compound Eye | These bee eyes are made of many light detectors is called ommatidia. |

| Ocellus | These bee eyes are used to detect motion. (Plural: ocelli) |

| Antenna | A movable segmented feeler that detects airborne scents and currents. |

| Labrum | Mouthpart that can help handle food and that forms the top of the feeding tube. |

| Mandible | Strong outer mouthpart that helps protect the proboscis. |

| Maxilla | Mouthpart beneath the mandible that can handle food items. |

| Labial Palp | This mouthpart is used to feel and taste during feeding. |

| Proboscis | Tube-like mouthpart used to suck up fluids. |

| Glossa | An insect’s hairy tongue can stick to nectar to pull it in toward the mouth. |

Interior Elements Of Honey Bee Anatomy

| Proboscis | Straw-like mouthparts of bees. Used to drink fluids. |

| Maxillae | The outer sheath of the proboscis surrounds the labium. |

| Mandible | A pair of jaws is used to chew pollen and work wax for comb building. They also help with anything that the bee needs to manipulate. |

| Labrum | A movable flap on the head that covers the opening of the food canal and proboscis |

| Food Canal | Like our mouths, this is the opening by which the bee will take in food. Bees’ food is almost always liquid in the form of nectar or honey. |

| Pharynx | Muscles are used to move the labium and suck up nectar from flowers.\ |

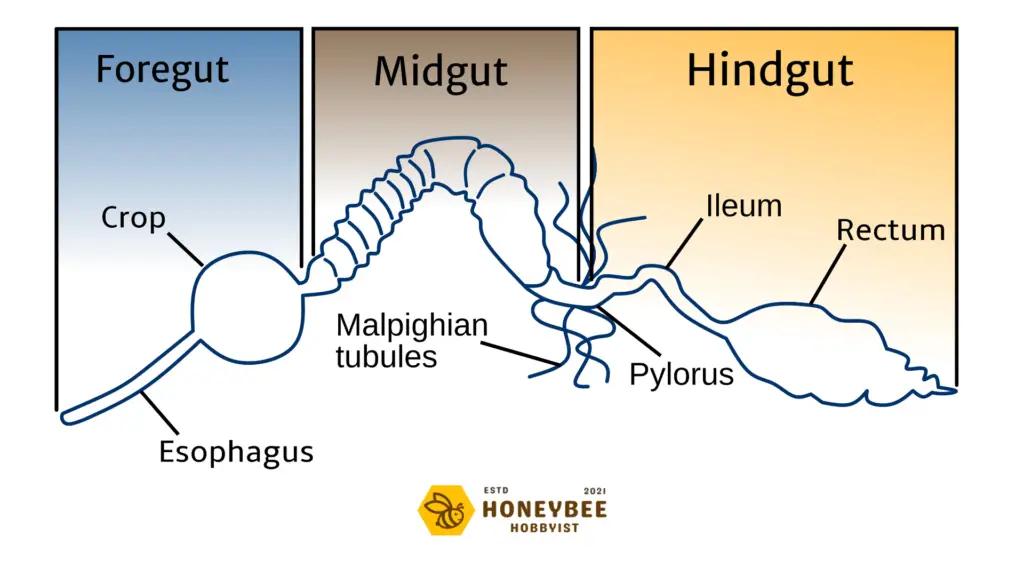

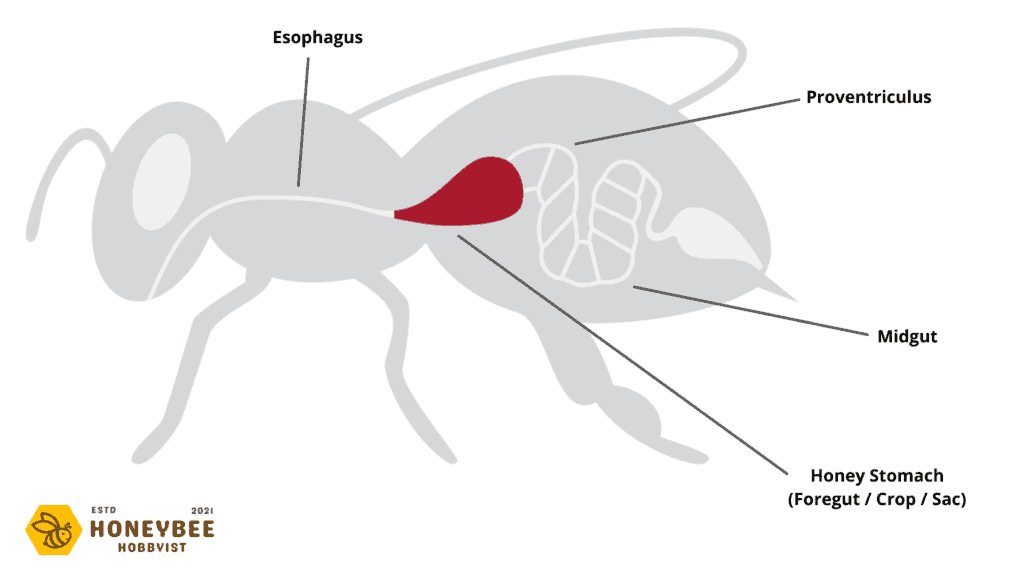

| Esophagus | The hollow tube through which ingested fluids pass to the honey stomach and later the midgut. |

| Hypopharyngeal gland | The gland that produces some compounds necessary for making royal jelly is used to feed the larvae. |

| Brain | Honey bees have excellent learning and memory processing abilities. Their brain processes information used in navigation and communication as well as memory. The brain also controls many of the basic bee body functions. |

| Salivary Gland | The salivary glands have several functions. Like the hypopharyngeal gland, the salivary glands produce some compounds necessary for creating royal jelly. The salivary glands produce liquid used to dissolve sugar, and also produce compounds used to clean the body and contribute to the colony’s chemical identity. |

| Flight Muscles | The thorax muscles, power the bee’s wings for flying and movement. These muscles work very hard and can help the bee to beat its wings up to 230 times per second. |

| Heart | Unlike mammals, honey bees and insects have an open circulatory system, meaning their blood is not contained within tubes like veins or arteries. The blood, or hemolymph, in insects is free-flowing throughout the body cavity and is pumped via the heart. The heart is the structure in red and acts as a pumping leaky tube to help move the hemolymph throughout the body |

| Opening of Spiracle | The respiratory system in insects is a series of hollow tubes connected to air sacs in the body. The openings of these hollow tubes are called spiracles. The tubes are called the trachea, which then provides oxygen and gas exchange to all tissues in the body. |

| Air sac | Air-filled sacs are used as reservoirs of air in the insect body. |

| Midgut | Contains the proventriculus, ventriculus, and small intestine. This is where most of the digestion and nutrient absorption occurs in the insect body |

| Heart Openings | Openings in the heart tube take in and pump out hemolymph. |

| Ileum | This short tube connects the midgut to the hindgut. The Ileum also often houses microbes, which aid in digestion. |

| Malpighian Tubules | A set of small tubes that are used to absorb water, waste, and salts, and other solutes from the body fluid, and remove them from the body. |

| Rectum | The rectum acts like our large intestine and is the bee’s primary location of water absorption for the gut after digestion and nutrient absorption. |

| Anus | The exit of the digestive system is used to excrete food waste (poop) while in flight. |

| Stinger | Also called “sting” is used to puncture the skin and pump venom into the wound. In worker bees, the stinger has a barbed end. Once pushed into the skin the stinger remains in the victim. The venom sac will stay with the stinger. If left in the body the stinger will continue to pump venom from the venom sac into the victim. Queen bees have a more extended and un-barbed stinger. Drones (males) do not have a stinger. |

| Stinger Sheath | The hardened tube, from which the stinger can slide in and out. |

| Sting Canal | The sting is hollow, allowing the venom to pass through the stinger. This is also the canal via which an egg is passed when the queen lays an egg. |

| Venom Sack | Holds the venom produced by the venom gland, and can then contract to pump venom through the stinger. |

| Venom Gland | This gland produces the venom that damages tissue if injected into the body. |

| Wax Glands | Worker bees start to secrete wax about 12 days after emerging. About six days later the gland degenerates and that bee will no longer produce wax. The queen is continually laying eggs to maintain colony size and to produce more new workers that produce wax. |

| Ventral Nerve Cord | Like the nerve cord in our spine, which holds bundles of nerve fibers that send signals from our brain to the rest of our body. |

| Proventriculus | A constricted portion of the honey bee foregut or honey stomach, which can control the flow of nectar and solids. This allows honey bees to store nectar in the honey stomach without being digested. It is part of the reason there is some confusion about whether honey is bee vomit. |

| Honey Stomach (Foregut/Crop) | This storage sac is used by honey bees to carry nectar. The honey stomach is hardened to prevent fluids from entering the body at this location. |

| Aorta | A blood vessel located in the back of a bee carries blood from the heart to the organs. |

| Esophagus | Part of the bee digestive system begins below the mouth and connects to the honey stomach. |

| Ventral Nerve Cord | Same as 27. This is a large bundle of nerves from the brain that sends signals to the rest of the bee’s body. |

| Labium | In bees, a tongue-like appendage is used to help drink up nectar. Like our tongue bees can taste with this organ. The labium fits inside of the maxilla (2), kind of like a straw. |

Honeybee Digestive System

The digestive system of the honeybee is unique, in that bees do not pee. They excrete a mixture of poop and roughly 10% of the moisture they consume.

Here is a simple look into how the honeybee’s digestive system works;

- Foregut or fore intestine: Consists of the bee’s mouth, esophagus, and honey stomach or crop.

- Midgut or middle intestine: Includes the bee’s “real stomach,” which digests food.

- Hindgut or hind intestine: Includes the small intestine and rectum.

Workers, Drones & Queens: Differences

Honeybee colonies are built upon a caste system in which three distinct roles are present.

A single female queen bee, tens of thousands of female worker bees, and hundreds (even thousands) of male drone bees, all work in harmony to maintain the health of the hive.

The numbers of worker and drone bees will vary based on colony size, time of year, and health of the hive.

Let’s walk through the differences in honey bee anatomy, as well as the roles, of each caste in the colony.

Queen Bees

The single female queen bee is often the largest in size, due to her long tapered abdomen. Her wings are often shorter than her abdomen.

The role of the queen bee is to mate with the drone bees and lay thousands of fertilized and unfertilized eggs each day. Fertilized eggs turn into worker bees, while unfertilized eggs turn into drone bees.

Besides her exterior features, Queen bees also have different reproductive organs than the worker and drone bees.

After mating with the drone bees, their spermatozoa are moved into the spermatheca gland where they remain for the life of the queen (usually up to 5 years).

Click here to read and see the difference between a queen bee and worker/drone bees.

Drone Bees

Drone bees are males only and do not have a stinger. Their larger eyes are used during the mating flight. Additionally, their wings are as long as their bodies, and their abdomens are blunt-tipped.

During the mating flight, the drone’s penis bulb is discharged into the queen’s vaginal pouch, with the male penis being torn from the male at the penis neck and remaining in the queen’s vaginal pouch. The drone then bleeds to death.

The queen may mate with several drones during the flight.

Worker Bees

Worker bees are females only, with the express role of collecting pollen and nectar for the production of honey and care of the hive.

To learn more about the honey production process, including how the honey stomach is used to transport nectar, click here.

The reproductive tract of the worker bee develops in the stinging gland. Along with the stinger, two glands (poison and alkaline glands) combine to give each sting 150mg of venom. Once the stinger is used, it is left in the victim and the bee dies.

If you’re interested in learning more about honey bee biology, we recommend reading “Honey Bee Biology and Beekeeping“, one of the books on our list of the best books about beekeeping.